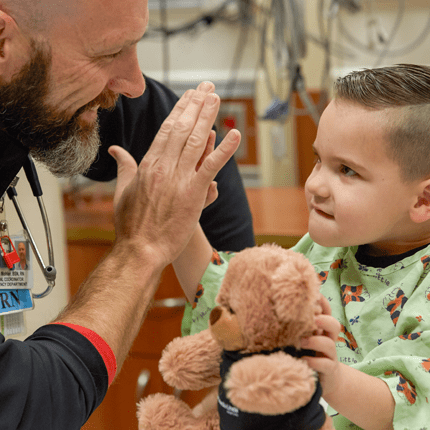

Hunter's Story

Jun 6, 2019Rare Epilepsy Surgery Makes All the Difference for Patient with Landau-Kleffner Syndrome (LKS)

When Dawn Oginsky, of Flushing, Mich., was in bed with her six-year-old son Hunter and his brother in May of 2009, she didn’t think much of the strange noises he was making, discounting it as a nightmare. But when Hunter started twitching, Dawn whose sister had epilepsy but outgrew it, immediately knew he was having a seizure.

Dawn and her husband William took Hunter to their local hospital and doctors conducted Electroencephalography (EEG) testing which records a patient’s brain wave activity. Doctors confirmed seizure activity. “Hunter had also been drooling and had staring episodes a few weeks prior to the seizure in his sleep. Because doctors determined Hunter had more than one seizure, the diagnosis of epilepsy was confirmed,” says Dawn.

Hunter, who one year earlier, was diagnosed with Kawasaki Disease, an autoimmune disorder often marked by persistent high fever, red eyes and other temporary symptoms, seemed to be managing fine from that diagnosis. However, potentially serious cardiac conditions including aneurysms are associated with Kawasaki Disease and testing was done to make sure he did not have an aneurysm which could cause seizure activity.

Hunter was put on a variety of medications to try to manage his seizures, but the medications were not successful and seemed to cause speech and memory problems. After further testing, a neurologist at their local hospital had a suspicion that Hunter may have Landau-Kleffner Syndrome, (LKS), a rare disorder causing gradual or sudden loss of the ability to understand and use spoken language. According to the National Institutes of Health, children with LKS, normally develop symptoms between five and seven years of age. Typically, they develop normally but then lose their language skills for no apparent reason. Many will also develop seizures.

The local doctor in Flint suggested that the Oginsky family go to DMC Children’s Hospital of Michigan for further testing since the disease is so rare. “We were told that many neurologists may never see a case of LKS,” says Dawn.

Hunter was seen by a Children's Hospital of Michigan neurologist who conducted extensive testing to pinpoint what might be causing his seizures.

The Children’s Hospital of Michigan is internationally known for pediatric epilepsy testing, treatment and research. The program utilizes advanced neuroimaging technologies – including a 3.0 Tesla Pediatric MRI scanner and one of the world’s few pediatric PET centers. Neurologists at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan use PET scanning and advanced EEG techniques to pinpoint the origin of epileptic seizures – enabling neurosurgeons to remove the affected tissue and dramatically improve the patient’s condition.

After extensive testing, it was confirmed that Hunter had LKS. In the meantime, medications and other treatments were not effective and his speech and language problems were becoming profound. “He couldn’t even say the alphabet. It simply broke our heart to see our son, who went from normal speech development to not being able to talk, pronounce words or even follow directions,” says Dawn.

The neurologist explained to Dawn and William that because the disease was so rare there were not many proven treatments. “Basically, he said Hunter could go on medication or try experimental surgery.”

Hunter’s case was discussed with the epilepsy surgery team which meets once a week to discuss potential candidates for epilepsy surgery. The team consists of neurologists (epileptologists), neurosurgeons, electroencephalographers, neuropsychologists, neuropathologists, epilepsy nurses, and others interested in the program including residents and students who attend to learn.

It is estimated that less than 10 surgeries of this type for children with LKS are performed each year in the U.S..

Dawn says after discussing the situation with the doctors, they knew what they had to do. “We knew the medications had not worked in the past, so we took a leap of faith, knowing we were in the best hands possible at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan and we decided to go with the rare surgery.”

Sandeep Sood, MD, neurosurgeon, Children’s Hospital of Michigan, who along with several members of the Neurology and Neurosurgery Department managed the treatment, says they were pretty confident about where the seizures were coming from. “We determined that the seizure activity was mostly concentrated on the left side of the brain that controls speech, vision and hearing”. A procedure called multiple subpial transactions was performed, which involves scraping, or making slits on the epileptic tissue to disconnect it, versus removing the tissue which is necessary for speech, vision and hearing. The surface of the brain was directly monitored with EEG recordings by Eishi Asano, MD., Ph.D. medical director of neurodiagnostics, during the procedure until the spikes were gone. When this happened, Dr. Sood stopped making the slits on the brain.L

After anxiously waiting for more than two hours during the procedure, the Oginsky family was elated to hear that the surgery was considered a success. “Prior to the surgery, his EEG showed spike and wave activity every three seconds, which can be a sign of seizure activity. After surgery, he had just one,” recalls Dawn, who also says there has been no evidence of further seizures since his surgery.

Since his surgery in March of 2011, Hunter has been doing exceptionally well. Hunter is very athletic and went from being in the state finals for wrestling to not winning any matches during this ordeal. “His dream has always been to be on the traveling baseball team and we are so proud that he is now on that team. He is able to follow directions and is back to reading. His speech therapy team was also amazed at his progress after only a couple of weeks after his surgery,” she says.

Dawn and William, who hope this story will raise awareness of this rare disease, says words cannot describe the gratitude they have for the medical team at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan. “They took a chance and they didn’t have to do that. Their care was exceptional in every way. They gave us our little boy back and for that we will forever be grateful.”